This is a massive project here in our stake. Two young moms, Melina Grahovac and Lisa Koy, got the idea of donating their children's outgrown clothes to refugee children. After I met them and we started talking about HOW, they organized this amazing project.

To watch the video, go to http://www.mormonnewsroom.org.uk/article/over-1000-welcome-bags-for-refugee-children . That is Michael Cziesla, our Stake President speaking.

http://www.presse-mormonen.de/artikel/welcome-bags-frankfurt

English translation follows the German original.

Plana-Garcia sagte: "Wir sind dankbar für alle Spenden, die wir erhalten haben. Freunde, Kollegen, Bekannte, Nachbarn, Kita-Eltern, Kirchenmitglieder - ohne ihre Unterstützung sowohl mit Spenden als ihre tatkräftige Mitarbeit, Zeit und Enthusiasmus hätten wir es nicht geschafft. Oft, wenn wir ihnen für ihre Mithilfe dankten, antworteten sie, dass sie uns danken sollten, weil wir es möglich machten. Die Menschen sind begierig zu helfen, wenn jemand es organisieren kann."

Wie sehr sich dieses Gefühl bewahrheiten würde, konnte man an den überwältigenden Spenden der einzelnen Menschen und vor allem auch dem Großteil der spendenden andersgläubigen Freunde erkennen, die mit ihren kleinen und teilweise auch sehr großen Spenden das Projekt in dieser Ausprägung erst möglich gemacht haben. Koy bezeichnete die Aktion und die Großzügigkeit der Menschen wiederholt als "wundervoll": "Weil Menschen auf ihr Gefühl und Eingebungen gehört haben, konnte durch viele kleine Dinge etwas Großartiges entstehen! Es war unglaublich zu sehen, wie der Himmlische Vater arbeitet - ich persönlich habe noch nie so viele Wunder in so kurzer Zeit erlebt!"

Schlüsselfiguren bei der Organisation dieses Projekts waren neben Melina Grahovac, Lisa Koy und Nerea Plana-Garcia folgende Personen: Rebecca Holt Stay, Ria Limam, Yvonne Bausmann, Marianne Heißer, Corinna Trindeitmar, Dana Pease, Boris Borm (Fotograf), Richard Clabaugh und Marilyn Caracena.

Organisationen wie LDS Charities, die Food Nanny, dem Träger für Kinderbetreuung BVZ und deren Einrichtungen, der Osterkindergarten Frankfurt, der Evangelischen Familien, der Kleiderkammer Neu-Isenburg, das Regierungspräsidium Gießen, der AfaA in Bitburg, der Mother’s Corner und Expats Baby Frankfurt gilt ebenfalls großer Dank für Spenden und Unterstützung.

Plana-Garcia ermutigt die Menschen in der Kirche und allen, die helfen möchten, mit folgenden Worten: "Wir müssen denen, die in Not sind, helfen. Während wir nicht die Welt ändern können (zum Beispiel die tragischen Umstände, die Menschen zur Flucht aus ihren Heimen zwingt) können wir einen Unterschied in unserem Umfeld machen. Wenn wir das tun, können wir andere inspirieren, die - zur gleichen Zeit - wieder andere inspirieren und so weiter. Sei ein aktiver Spieler im Leben."

English translation: notes in [brackets] are mine. RHS

To watch the video, go to http://www.mormonnewsroom.org.uk/article/over-1000-welcome-bags-for-refugee-children . That is Michael Cziesla, our Stake President speaking.

http://www.presse-mormonen.de/artikel/welcome-bags-frankfurt

English translation follows the German original.

27 APRIL 2016 - FRANKFURT

Aktion "Welcome Bags for Refugee Children"

in Frankfurt am Main: 1.061 Taschen gespendet

Am Donnerstag, den 21. und Freitag, den 22. April 2016, fand in der Gemeinde Frankfurt der Kirche Jesu Christi der Heiligen der Letzten Tage ein Hilfsprojekt der besonderen Art statt. Für sechs Erstaufnahmeeinrichtungen für Flüchtlinge in Hessen und Rheinland-Pfalz packten unzählige Helfer 1.061 "Welcome Bags". Diese Willkommenstaschen für Kinder bis zwölf Jahren wurden in den darauffolgenden Tagen in den Einrichtungen in Bitburg, Büdingen, Gießen, Kusel, Neustadt und Rotenburg verteilt.

Initiatorin Melina Grahovac, Beauftragte für die jungen Mütter in ihrer Gemeinde, und Lisa Koy, ihre Assistentin, veranstalteten unter anderem im letzten Sommer Tauschbasare für Kinderkleidung. Der Großteil der übriggebliebenen Kleidung wurden danach an Bedürftige oder Flüchtlinge abgegeben. Dort formte sich zuerst der Gedanke, auch etwas für die Kinder der Flüchtlinge in der Region zu tun.

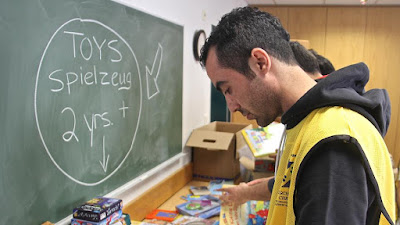

| 1 von18 | Freiwillige Helfer in Frankfurt am Main sortieren Sachspenden für Flüchtlingskinder. © 2016 Intellectual Reserve, Inc. Alle Rechte vorbehalten. |

Bei dem zuletzt stattfindenden Basar in der Mehrzweckhalle im Gemeindehaus der Gemeinde Frankfurt bot Schwester Rebecca Holt Stay, Koordinatorin für Flüchtlingshilfe in Europa, ihre Hilfe an. Daraufhin beschloss Grahovac, dass jetzt der richtige Zeitpunkt sei, zu helfen und gemeinsam mit Koy und Nerea Plana-Garcia, der zweiten Ratgeberin in der Leitung der örtlichen Frauenhilfsvereinigung, die Kampagne "Welcome Bags for Refugee Children" zu starten. Grahovac stellte fast alle Kontakte zu den Erstaufnahmeeinrichtungen selbst her und fragte gemeinsam mit ihren Helferinnen bei vielen Organisationen und Firmen an, ob diese bereit wären, zu spenden oder zu helfen.

|

| Sister Caracena : she sorted donations as they came in for weeks |

Freunde, Kollegen, Eltern einer Kindertageseinrichtung und eine Grundschule hätten sich begeistert bereiterklärt zu spenden, vorausgesetzt, jemand würde die Planung in die Hand nehmen, so Grahovac.

Christopher Guthier, einer der Helfer, erklärte, er selbst und viele andere hätten einfach nach einem Türöffner gesucht, der es möglich machte, zu helfen. Grahovac war zwei Tage mit ihren beiden Kindern vor Ort und trug ihre jüngste Tochter beim Organisieren und Verpacken größtenteils auf dem Rücken trug.

|

| Nerea and Sister Hacking, who has been coordinating our arts and crafts in Limburg camp. |

Plana-Garcia sagte: "Wir sind dankbar für alle Spenden, die wir erhalten haben. Freunde, Kollegen, Bekannte, Nachbarn, Kita-Eltern, Kirchenmitglieder - ohne ihre Unterstützung sowohl mit Spenden als ihre tatkräftige Mitarbeit, Zeit und Enthusiasmus hätten wir es nicht geschafft. Oft, wenn wir ihnen für ihre Mithilfe dankten, antworteten sie, dass sie uns danken sollten, weil wir es möglich machten. Die Menschen sind begierig zu helfen, wenn jemand es organisieren kann."

Ursprünglich geplant waren 500 Welcome Bags für Kinder, doch die Anzahl der Welcome Bags wurde aufgrund des großen Bedarfs der Erstaufnahmeeinrichtungen erhöht.

"Wir haben uns bemüht, dieses Ziel erreichen zu können“, meinte Koy. "Dass die Leute so großzügig spenden würden, konnten wir zu dem Zeitpunkt allerdings noch nicht wissen. Wir hatten nur das Gefühl, dass über 1.000 Taschen möglich gemacht werden könnten."

|

| Elias, from Iran, joined the church in January and just baptized his friend Mohammed last week |

Wie sehr sich dieses Gefühl bewahrheiten würde, konnte man an den überwältigenden Spenden der einzelnen Menschen und vor allem auch dem Großteil der spendenden andersgläubigen Freunde erkennen, die mit ihren kleinen und teilweise auch sehr großen Spenden das Projekt in dieser Ausprägung erst möglich gemacht haben. Koy bezeichnete die Aktion und die Großzügigkeit der Menschen wiederholt als "wundervoll": "Weil Menschen auf ihr Gefühl und Eingebungen gehört haben, konnte durch viele kleine Dinge etwas Großartiges entstehen! Es war unglaublich zu sehen, wie der Himmlische Vater arbeitet - ich persönlich habe noch nie so viele Wunder in so kurzer Zeit erlebt!"

Neben den Spendern registrierten sich mehr als 200 helfende Mitglieder und vor allem andersgläubige Freunde an den beiden Tagen, um Kleidung zu sortieren und zu packen. Neben den Pfählen Frankfurt, Friedrichsdorf und Kaiserslautern halfen auch die Mitglieder der Gemeinden Krefeld und Koblenz an der Hilfsaktion engagiert mit.

Die Kirche Jesu Christi der Heiligen der Letzten Tage stellte 300 Fleecedecken, 1.061 Handtücher, 1.700 kleine Packungen Feuchttücher, 670 Packungen Windeln und 422 Unterwäsche-Sets zur Verfügung. Weitere etwa 200 Packungen Windeln wurden zudem von privaten Spendern übernommen gestiftet.

|

| Elder Young, who is a really helpful tech elder who assists us with computer work in our offices on Wednesdays: he worked for two full days sorting. |

Zur Freude aller Beteiligten erklärten sich auch einige Firmen bereit, zu helfen. Ikea spendete etwa 750 der Taschen, in welche die Spenden verpackt wurden und zusätzlich noch Buntstifte, Filzstifte und Blöcke. 284 Taschen wurden von anderen Personen zusätzlich gekauft. Die Firma Faber-Castell beteiligte sich mit Stiften, Anspitzern und Radiergummis, Playmobil verschenkte Spielzeugfiguren. Von Ria Limam, die sich privat bei Flüchtlingsprojekten engagiert, wurden 760 Decken, die ursprünglich von der Deutschen Lufthansa gespendeten worden waren, zur Verfügung gestellt.

Insgesamt wurden drei Europcar-Transporter zur Verfügung gestellt. Zwei davon wurden von Dimension Data finanziert, der dritte Transporter wurde von Europcar kostenlos als Spende gestellt. Die Brüder Christopher und Florian Guthier, beide Angestellte von Dimension Data und Ruben Marzolla halfen beim Transport der Spenden. Die Benzinkosten wurden von der Kirche übernommen.

|

| Sister Robertson and her son, age 8. |

Schlüsselfiguren bei der Organisation dieses Projekts waren neben Melina Grahovac, Lisa Koy und Nerea Plana-Garcia folgende Personen: Rebecca Holt Stay, Ria Limam, Yvonne Bausmann, Marianne Heißer, Corinna Trindeitmar, Dana Pease, Boris Borm (Fotograf), Richard Clabaugh und Marilyn Caracena.

|

| me |

Organisationen wie LDS Charities, die Food Nanny, dem Träger für Kinderbetreuung BVZ und deren Einrichtungen, der Osterkindergarten Frankfurt, der Evangelischen Familien, der Kleiderkammer Neu-Isenburg, das Regierungspräsidium Gießen, der AfaA in Bitburg, der Mother’s Corner und Expats Baby Frankfurt gilt ebenfalls großer Dank für Spenden und Unterstützung.

Plana-Garcia ermutigt die Menschen in der Kirche und allen, die helfen möchten, mit folgenden Worten: "Wir müssen denen, die in Not sind, helfen. Während wir nicht die Welt ändern können (zum Beispiel die tragischen Umstände, die Menschen zur Flucht aus ihren Heimen zwingt) können wir einen Unterschied in unserem Umfeld machen. Wenn wir das tun, können wir andere inspirieren, die - zur gleichen Zeit - wieder andere inspirieren und so weiter. Sei ein aktiver Spieler im Leben."

1,061 bags donated at "Welcome Bags for Refugee

Children“ campaign

„My

brothers and sisters, our opportunities to shine surround us each day, in

whatever circumstance we find ourselves. As we follow the example of the

Savior, ours will be the opportunity to be a light in the lives of others,

whether they be our own family members and friends, our co-workers, mere acquaintances,

or total strangers.“ – President Thomas S. Monson, General Conference, October 2015

|

| Elder Stay putting new books into the bags |

Friday, 23 April 2016 – On the 21st and 22nd of

April a very special aid project took place at the Frankfurt 1st and 2nd Wards of the Church

of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints. For six ireception camps for refugees [where the refugees stay until their paperwork is processed and they are given an apartment] in

Hessen and Rheinland-Pfalz including Bitburg, Büdingen, Gießen, Kusel, Neustad

and Rotenburg 1,061 Welcome Bags for all Primary children (0 – 12 years) have

been packed by countless helpers and were distributed to the camps at the 23rd of April.

Initiator Sister Melina Grahovac, Relief Society coordinator for Young Mothers of the Church and Sister Lisa Koy, her friend, organised a clothing exchange for childrens clothing last summer. 'Most of the unwanted clothing was donated to the needy and refugees. At that time, the thought came to do also something for the refugee children in the local

area, but that idea was not pursued.

|

| Our poster |

At the March clothing exchange in the Frankfurt wards, Sister

Rebecca Holt Stay, coordinator for all LDS Church Refugee Aid in the Europe Area, had the feeling that she needed to go to the bazaar and walked over there from her office., where she met Sister Grahovac and Sister Koy in the foyer.

As she heard their thoughts about helping refugee children, she

offered her help. That same night Sister Grahovac felt powerfully that this was the

right time to help, that she needed to act. Together with Sister Koy and Nerea Plana-Garcia, second counselor of the Women's Relief Society in the Frankfurt 1st Ward, she

decided to start the "Welcome Bags for Refugee Children“ campaign.A Facebook page was started with links to spreadsheets of what donations were needed. Sister

Grahovac spent a lot of time connecting with the responsible people at the

refugee camps and, supported by her helpers, also got in touch with countless

organisations and companies to ask for help and donations.'

Later Sister Grahovac said that friends, colleagues, kindergarten parents and a primary school were enthusiastic about helping – on the condition that someone else would organize the whole campaign.

|

| Lots of great online resources were used. |

Later Sister Grahovac said that friends, colleagues, kindergarten parents and a primary school were enthusiastic about helping – on the condition that someone else would organize the whole campaign.

Brother Christopher Guthier, one of the many

helpers who drove one of the trucks to two camps, repeatedly said, that people, including himself, were searching for a

door opener like this campaign, which would make it possible to help. It

should be mentioned that Sister Grahovac had her two children with her during the entire final two days of sorting, organizing and packing the donations, carrying her youngest

daughter on her back almost the whole time. The joining of her faith and her

love for the refugees affected and united the people around her noticably. Everyone smiled the whole two days.

Also Nerea Plana-Garcia, Second Counselor of

the Relief Society, who was helping during the project, said:

"We are

grateful for all the donations that we received. Friends, colleagues,

aquaintances, neighbours, kindergarden parents, church members ... Without

their support both in donations of goods and as well as their hands, time and

enthusiasm, we could not have accomplished it.

Often, when thanking them for their collaboration, they replied that

they should thank ME for making it possible for them to help. People are EAGER

to help if someone else organises it.“

|

| Typical of the donations: people gave really nice stuff |

„We have

endeavored to reach this goal“, wrote Sister Koy, who was supporting Sister

Grahovac energetically. „We couldn’t know at that time that people would donate

so generously. We just had the feeling, that more than 1,000 bags would be

possible.“

How much

this feeling was proven right, was shown by the overwhelming amount of

donations of individual members and also the large number of donating

non-members, who made the project in this form possible in the first place by

small. There were also some very large donations. Sister Koy designated the campaign and the

generosity of the people repeatedly as WONDERFUL!:

"Because

people listened

to their feelings and inspirations, something great could be achieved by many

small things! It was unbelievable to see how Heavenly Father works – I

personally have never experienced so many miracles in such a short time!“

Besides the donors, more than 200 members and many non-members registered to sort out the donations and to

pack the welcome bags. In addition to Frankfurt, Friedrichsdorf and

Kaiserslautern stakes, members of the Krefeld and Koblenz wards helped considerably on this project.

„The wonder of the campaign was the

overwhelming help of members and non-members. Every individual has made this

project possible with their donation.“

The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day

Saints provided 300 fleece blankets, 1,061 towels, 1,700 small packages of

wipes, 670 packages of diapers (further generous donations of an additional 200 packages of diapers were made by private donors) and

422 underwear sets.

To the delight of the participants some

firms agreed to help. IKEA donated approximately 750 of the bags, in which all

donations were packed. They also provided coloured crayons, felt pens and

sketch pads. 284 IKEA bags were bought by individuals. FABER-CASTELL donated pencils, sharpeners and erasers, PLAYMOBIL donated toy

figures. Ria Limam, who is privately involved in refugee work, provided boxes full of children's clothing and 1000 blankets which were originally donated by Lufthansa (the nice ones from 1st class!)

Altogether three Europcar delivery trucks were

made available to deliver all the bags. Two of them were funded by Dimension Data, the use of the third one was a

gift from Europcar. The brothers Christopher and Florian Guthier, both

employees of Dimension Data and brother Ruben Marzolla helped with the

transport and the distribution of the welcome bags. Fuel costs were covered by

the Church.

Key players in the organisation of the project were – next to Melina Grahovac, Lisa Koy and Nerea Plana-Garcia – following persons: Rebecca Holt Stay, Ria Limam, Yvonne Bausmann, Marianne Heißer, Corinna Trindeitmar, Dana Pease, Boris Borm, Richard Clabaugh and Marilyn Caracena.

|

| LDS warehouse workers making the delivery of pallets of diapers |

Key players in the organisation of the project were – next to Melina Grahovac, Lisa Koy and Nerea Plana-Garcia – following persons: Rebecca Holt Stay, Ria Limam, Yvonne Bausmann, Marianne Heißer, Corinna Trindeitmar, Dana Pease, Boris Borm, Richard Clabaugh and Marilyn Caracena.

Thanks for donations and support are also

extended to organizations like LDS Charities, the Food Nanny, the Träger für

Kinderbetreuung BVZ and their establishments, the Osterkindergarten Frankfurt, the

Evangelische Familienhilfe, the Kleiderkammer Neu-Isenburg, the

Regierungspräsidium Gießen, the AfaA in Bitburg, the Mother’s Corner and Expats

Baby Frankfurt.

Sister Nerea Plana-Garcia encourages members

of the Church and all people who are eager to help with following words:

„We must

help those in need. While I cannot change the world (i.e the tragic

circumstances which made them flee from their homes) I can make a difference in

my environment. By doing that, I can inspire others, who – at the same time –

can inspire others and so on. Be an active player in life.“

More impressions and informations of the

Welcome Bags for Refugee Children campaign you find on the official facebook

page:

https://www.facebook.com/Welcome-Bags-for-Refugee-Children-1582869458699160/?fref=ts

https://www.facebook.com/Welcome-Bags-for-Refugee-Children-1582869458699160/?fref=ts